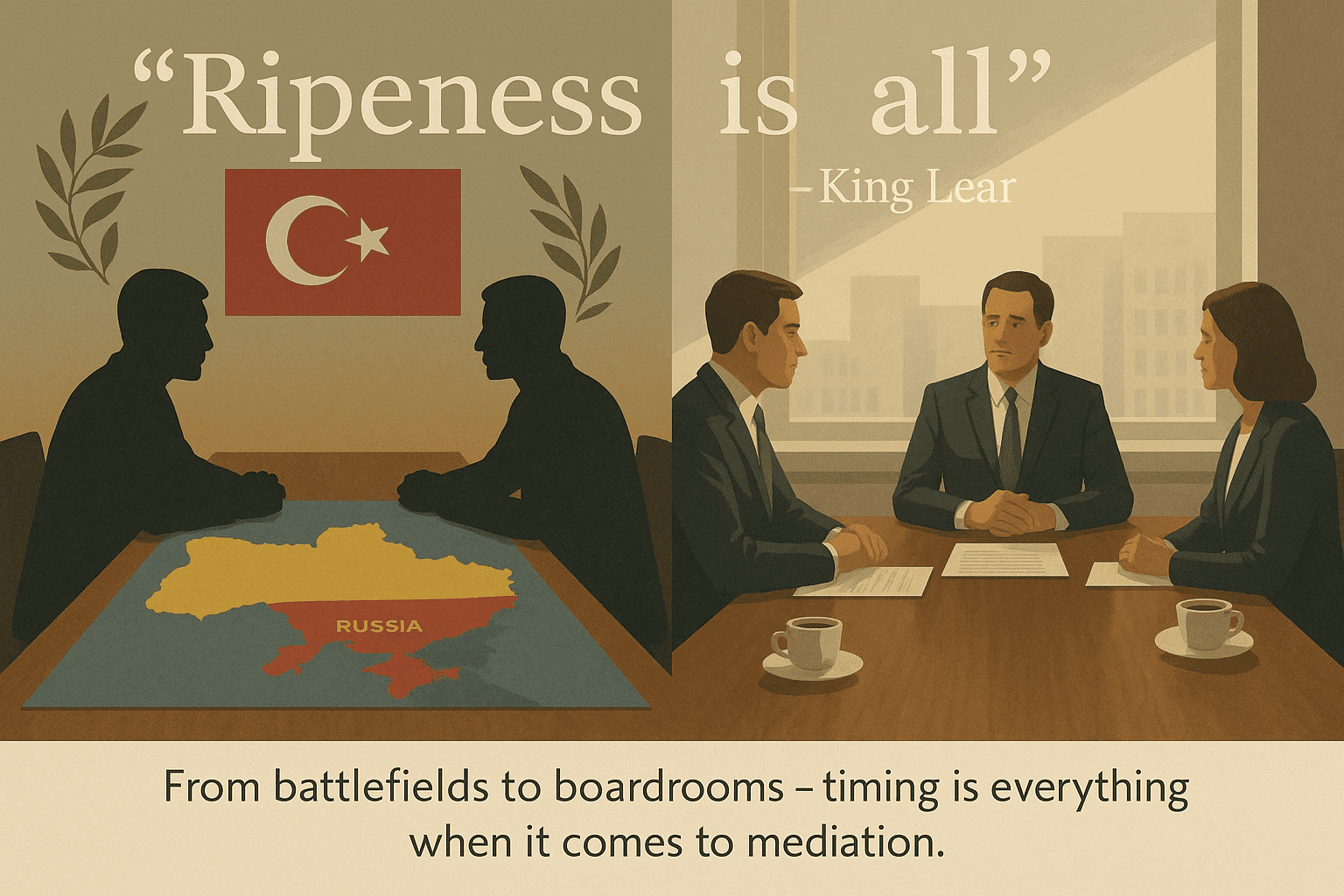

“Ripeness Is All”: When Should Commercial Litigators Advise Clients to Mediate?

By Peter Causton

Everyone knows that the war in Ukraine will one day come to an end. History tells us that even the most entrenched conflicts ultimately find their way to a table — if not of peace, then of pragmatic necessity. What no one knows is when that moment will come. Is now the time for Putin to sit down with Zelensky in Turkey to broker peace? Are the conditions right, or does each side still see more to gain from the battlefield than the negotiating room?

In Shakespeare’s King Lear, Edgar speaks the line: “Ripeness is all.” It is a phrase that resonates as much in geopolitics as it does in litigation. In commercial disputes, too, there is a moment when the dispute is “ripe” for resolution — when the cost, risk, and emotional toll of litigation finally outweigh the perceived benefits of continuing the fight.

As trusted advisers, commercial litigators must help their clients recognise that moment. Choosing the right time to mediate can make the difference between a swift, cost-effective resolution and years of costly, damaging conflict. So, when is the right time?

1. Early Mediation – Before Proceedings Are Issued

There are many benefits to engaging in mediation at the pre-action stage:

- Cost-efficiency: Settling early avoids issuing fees, disclosure battles, and the procedural treadmill of litigation.

- Confidentiality: A mediated agreement keeps sensitive commercial matters private — unlike judgments in open court.

- Preservation of relationships: Especially vital in ongoing commercial partnerships or joint ventures.

Pre-action correspondence may help clarify the dispute and set the stage for an effective early mediation. In some cases, simply receiving a well-drafted letter of claim and response may prompt parties to consider mediation seriously.

However, litigators must assess whether the dispute is “ripe” at this stage. Mediation too early — before the issues are defined or documents exchanged — may result in wasted costs if one or both parties are not ready to engage constructively.

2. After Disclosure or Key Evidence Exchange – The Strategic Middle Ground

Mediation tends to be most successful once the parties have exchanged statements of case, and particularly after disclosure or witness evidence has been served. This middle phase of litigation offers several advantages:

- Greater clarity: Both sides understand the merits and weaknesses of their positions.

- Client realism: Exposure to litigation costs and procedural complexity can temper expectations.

- Court encouragement: Many judges actively ask parties what steps they have taken to explore settlement.

At this stage, mediation is often viewed not as a sign of weakness, but as a prudent and strategic step. The court’s expectation that parties engage in ADR — in line with CPR 1.4 and PD 26 — makes this an ideal time to initiate or renew discussions.

3. Just Before Trial – The Courtroom Steps Syndrome

The pressure of an impending trial can concentrate minds. By this stage:

- Costs have escalated: Parties are deeply invested, financially and emotionally.

- Public exposure looms: Reputational risks may prompt a desire for private settlement.

- Judicial warnings intensify: Courts may penalise unreasonable refusals to mediate in costs, citing Halsey v Milton Keynes General NHS Trust and later authorities.

While settlements often occur at this late hour, this is not an optimal time. Parties are often entrenched, and the opportunity to craft a creative or commercial solution may have passed. It is better to “strike while the iron is warm” — not scalding.

4. When the Court Signals – Stay Proceedings or Risk Sanctions

In the post-Churchill v Merthyr Tydfil era, the judicial climate is shifting. Courts are increasingly inclined to require or strongly encourage mediation, even without party consent. Litigators must be alive to signals from the bench and proactively advise clients to mediate — not only to comply with procedural expectations, but to avoid adverse costs consequences.

Recent cases such as Assensus Ltd v Wirsol Energy Ltd show the court’s willingness to examine the reasonableness of a refusal to mediate in its costs rulings. Solicitors who wait too long to raise ADR may face difficult questions later.

5. When Circumstances Change – Responding to New Risks or Offers

Settlement opportunities can also arise mid-proceedings, especially when:

- A damaging disclosure or ruling has shifted the legal balance.

- A Part 36 offer creates real financial risk.

- A client’s appetite for litigation wanes under pressure.

Commercial litigators must be attuned to these inflection points. Recommending mediation at such a time shows strategic judgment — not indecision. Indeed, many disputes are resolved when clients feel they have nothing left to prove, but much still to lose.

Conclusion: Ripeness Requires Judgment

Like war, litigation has its rhythms — and its breaking points. Knowing when a dispute is “ripe” for resolution is part art, part science. It requires judgment, experience, and a deep understanding of your client’s commercial objectives.

Early mediation can be efficient and relationship-preserving. Mid-litigation mediation often yields the best results in terms of informed realism and judicial support. Late mediation may still succeed — but may come at the cost of missed opportunities and rising irrecoverable expense.

Ultimately, the best litigators don’t just prepare for trial — they prepare for resolution. And they know, to quote Lear, that in litigation as in life: “Ripeness is all.”