From Brentford County Court to a Saxon Synod: Lessons in Mediation

This morning I found myself at Brentford County Court, attending in the hope of helping resolve a modern property dispute. As I waited outside, my eyes wandered to the pink granite column standing nearby — a weathered monument commemorating a far older confrontation.

Its inscription tells of a time when Edmund Ironside drove King Cnut’s Danes across the Thames. But it also brought to mind another early medieval gathering held not far from here: a meeting in 781 between King Offa of Mercia and the Bishop of Worcester.

Their quarrel? Control over some of the most valuable land and church property in the kingdom — notably the monastery at Bath. It could easily have descended into force and confiscation. Instead, they convened a synod at Brentford, a neutral, strategically located meeting point between Mercia and the southern kingdoms. There, in the presence of senior clergy and noble advisers, an agreement was reached. Lands changed hands, charters were drawn up, and both sides left with a settlement they could at least publicly accept.

Was it “mediation” in the modern sense? Not quite — there was no trained neutral in a suit with a bundle of position papers — but the dynamics were strikingly similar:

- A neutral venue

- Both parties heard in front of respected third parties

- A recorded agreement rather than unilateral action

Fast forward to today, and here I was, steps away from that ancient tradition, attending court in the hope of avoiding a full trial. The lesson from both 781 and 2025 is the same: when property, relationships, and reputations are on the line, negotiation in a neutral setting can avoid years of hostility and the high cost of battle — whether with swords or with solicitors’ letters.

The stone outside Brentford County Court is a reminder that disputes are as old as the Thames itself. But it also reminds us that meeting to talk — and to listen — has always been the better way forward. If King Offa and a bishop with a monastery at stake could sit down in Brentford to thrash things out, surely so can we.

It certainly had many of the hallmarks of what we’d now call a mediation, even though in 781 it would have been framed as a royal council or synod decision rather than a neutral-facilitated settlement.

Why it resembles mediation

- Two parties in dispute – King Offa and Bishop Heathored of Worcester – over high-value assets (Bath minster and lands).

- Neutral venue – Brentford was neither in the heart of Mercia nor in Worcester’s immediate sphere, which avoided one party feeling at a territorial disadvantage.

- Facilitated resolution – A formal meeting (synod) brought together both sides in front of a broader body, which had authority to broker a settlement.

- Negotiated terms – The result was a recorded agreement/charter rather than a unilateral seizure, implying consent (even if consent was partly political pressure).

Who might have “mediated” in early medieval terms?

There was no professional mediator role then, but there were people and structures that performed a similar function:

- Archbishop of Canterbury – At the time, Jænberht was Archbishop (until 792). He was senior church authority in the south and often mediated between kings and bishops when disputes threatened church unity.

- Other senior bishops – Synods typically involved several bishops from across Mercia and Kent, whose collective moral authority could pressure both parties into settlement.

- Ealdormen and the king’s thegns – Nobles loyal to Offa but respected by the church could act as intermediaries.

- The synod itself as a corporate mediator – Early medieval councils often acted as a body to hear both sides, deliberate, and issue a settlement acceptable to both.

The likely dynamic

Offa was powerful enough to impose his will, but using a synod:

- Gave the settlement legitimacy in the eyes of the wider church.

- Avoided the appearance of outright confiscation.

- Allowed the church to present it as an internal resolution rather than royal coercion.

In modern language, this was a multi-party facilitated negotiation with binding minutes — in other words, functionally a mediation.

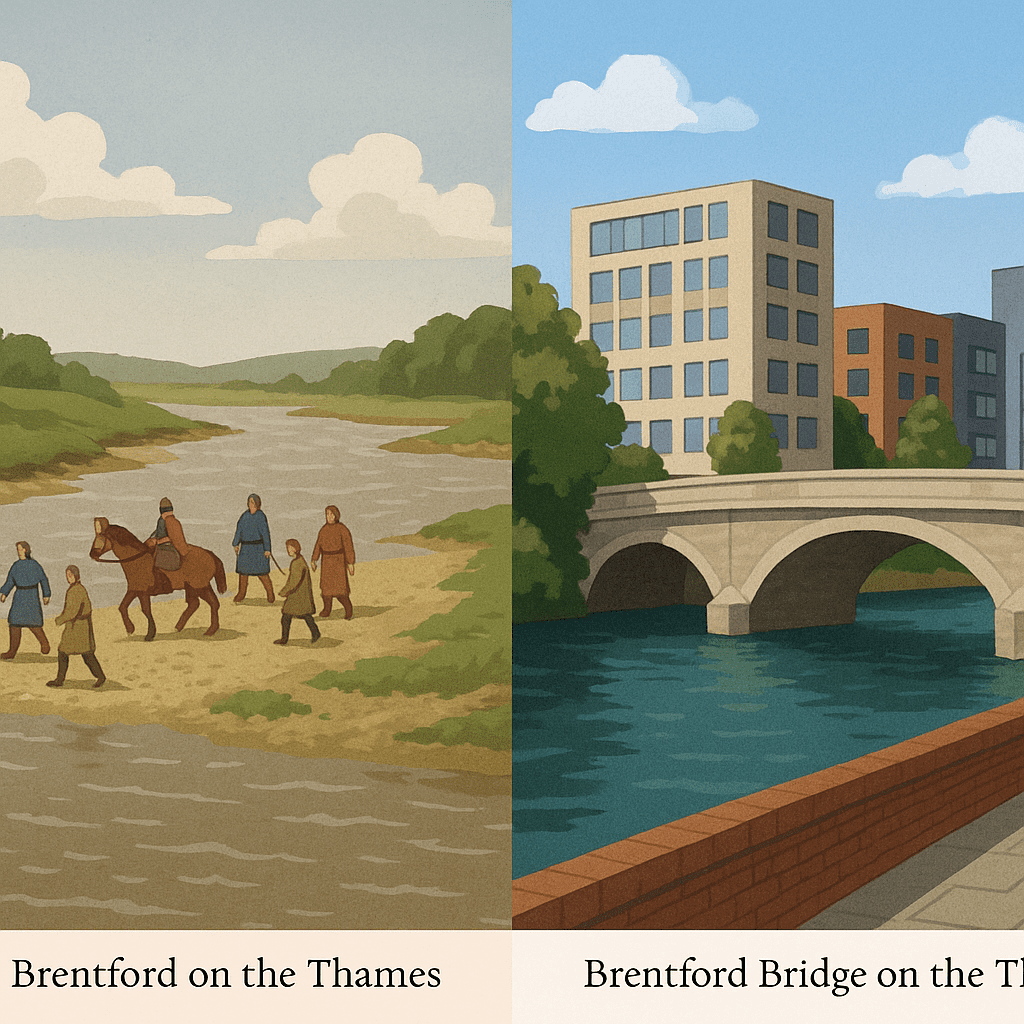

Why crossing was possible

• Tidal shallows – The Thames in the Brentford area was shallower and wider than today, with gravel and sand banks exposed at low tide.

• Roman ford – The Roman road from Londinium to Silchester (later the Bath Road) crossed the Thames here. Archaeological finds of gravel causeways and timber structures suggest a prepared ford existed.

• Place-name clue – Bregentford literally means “ford over the River Brent”. The Brent itself flowed into the Thames at the crossing, and fords were often sited where tributaries met the main river because the gravel fans made the water shallower.

⸻

Transition to bridges

By the medieval period, the ford was probably replaced or supplemented by a timber bridge (there’s reference to one by the 13th century). But in Offa’s time, travellers and traders — and perhaps Offa’s own synod party — would have arrived at a gravelled, shallow crossing point, possibly with causeways and ferries to help at high tide.

The Location: Brentford as a Neutral Meeting Place

Brentford—recorded as Bregentford in early sources—was an important Thames crossing where the River Brent meets the Thames. This ford was situated on a Roman road leading west from London, making it a strategic location and a de facto boundary marker between kingdoms. In early sources, it’s described as a convenient halfway meeting point for rival territories.

2. What Was There in 781?

- No abbey or castle existed at Brentford at that time. Castle construction only came later, post-Norman Conquest.

- There may not have been a formal church or minster building either—no definitive archaeological or documentary evidence survives of a Saxon church standing there. Historians suggest the gathering might have taken place outdoors or in a simple timber structure, perhaps associated with a local noble’s hall or a royal estate centre.

3. Why Brentford?

- Accessibility: Well-connected by river and road, Brentford was an obvious meeting point for people traveling from both Mercian and southern territories.

- Neutral ground: Its location—and possibly existing as a royal stopover—allowed both parties to meet without entering one another’s power base.

- Historic precedent: As early as 705, meetings between rival groups were documented at Brentford, likely due to the same neutral and boundary-crossing functions.

translated summary of the 781 Brentford charter (Sawyer S 1257), documenting the agreement between Bishop Heathored of Worcester and King Offa of Mercia:

⸻

Summary Translation of Charter S 1257 (781, Brentford)

Parties Involved

• Bishop Heathored of Worcester, with the consent of his clergy and officials.

• King Offa of Mercia.

Terms of the Agreement

• Heathored surrenders to Offa the minster at Bath along with 90 hides of land, plus an additional 30 hides by the River Avon.

• In return, Offa grants the bishopric land holdings in several locations:

• 30 hides at Stratford-upon-Avon (Warwickshire)

• 38 hides at Sture (possibly Kidderminster, Worcestershire, or Alderminster, Warwickshire)

• 14 hides at Stour-in-Ismere (likely in Worcestershire)

• 12 hides at Bredon (Worcestershire)

• 17 hides at Hampton Lucy (Warwickshire)

So essentially, Bath (with its lands) was exchanged for multiple estates, consolidating the bishopric’s holdings in a different region.

it looks like Offa got the prize asset: Bath Minster and its large, wealthy estate.

Relative value in 8th-century terms

1. Bath’s value

- 90 hides at Bath plus 30 hides by the Avon = 120 hides total.

- A “hide” was a notional unit of land assessment — often enough to support a household (roughly 120 acres, but it varied).

- Bath was an urbanised Roman site with a hot spring — a prestige minster, potentially a pilgrimage centre, with market tolls and royal guest facilities.

- The monastery controlled not just land but also the social and political capital of being a religious hub in a former Roman town.

2. The bishop’s new lands

- Total: 111 hides (30 + 38 + 14 + 12 + 17).

- These were rural estates scattered in the Avon–Severn area.

- Likely good farmland with agricultural rent and food renders, but without Bath’s strategic location or prestige.

- Being more compact in Mercian heartlands might have made them easier to administer, but they were less prominent.

3. Economic comparison

- In purely hide-for-hide terms: Bishop lost 120 hides, gained 111 — so even nominally a net loss.

- In prestige terms: The bishop ceded an ancient, Roman-linked ecclesiastical site to the king — the kind of asset rulers coveted to cement their dynastic and political power.

- The gain may have been more about consolidating lands nearer Worcester and reducing conflict with the king than about maximising income.

Why the bishop might have agreed

- Offa was extremely powerful and could have seized Bath outright. By negotiating, Heathored at least secured compensation.

- The exchange could remove contested territory from Worcester’s portfolio, avoiding ongoing royal interference.

- Being seen to “gift” Bath in a synod could preserve some church dignity and create a public record of royal generosity in return.

At first glance, the Brentford synod settlement between King Offa of Mercia and Bishop Heathored of Worcester looks heavily skewed in the king’s favour. Our valuation suggests:

- Bath & Avon lands given to Offa carried not only high farmland value but also urban and prestige assets — worth far more than the rural estates given in exchange.

Using a very rough silver-based conversion, the annual renders would compare like this:

- Bath & Avon lands (120 hides) ≈ £26,856/year (modern silver value equivalent)

- Bishop’s new lands (111 hides) ≈ £24,842/year

- Difference ≈ £2,014/year in the king’s favour

This only measures the raw agricultural/silver rent value.

It doesn’t factor in:

- Bath’s prestige, trading rights, and possible toll income from markets/pilgrims.

- Administrative efficiency — the bishop’s new lands were closer to Worcester.

- Political benefit — avoiding a direct clash with Offa may have been worth more than a few hides’ rent.

So why agree?

1. Political pressure

Offa was at the height of his power. Refusing him outright could have risked confiscation without compensation.

2. Strategic retreat

By trading Bath for estates nearer Worcester, the bishop consolidated his holdings, making them easier to defend and administer.

3. Public legitimacy

Settling at a synod, in the presence of church and noble witnesses, preserved an image of mutual consent and avoided open conflict.

4. Long-term survival

Church leaders often played the long game. Even a poor financial exchange could secure royal favour, which was vital for protecting other assets.

In modern mediation terms, the bishop accepted a suboptimal financial outcome to remove a powerful threat, gain certainty, and maintain working relations — a decision many parties still make in negotiation today.

.