Following in Family Footsteps: Inheritance, Inspiration or Nepotism?

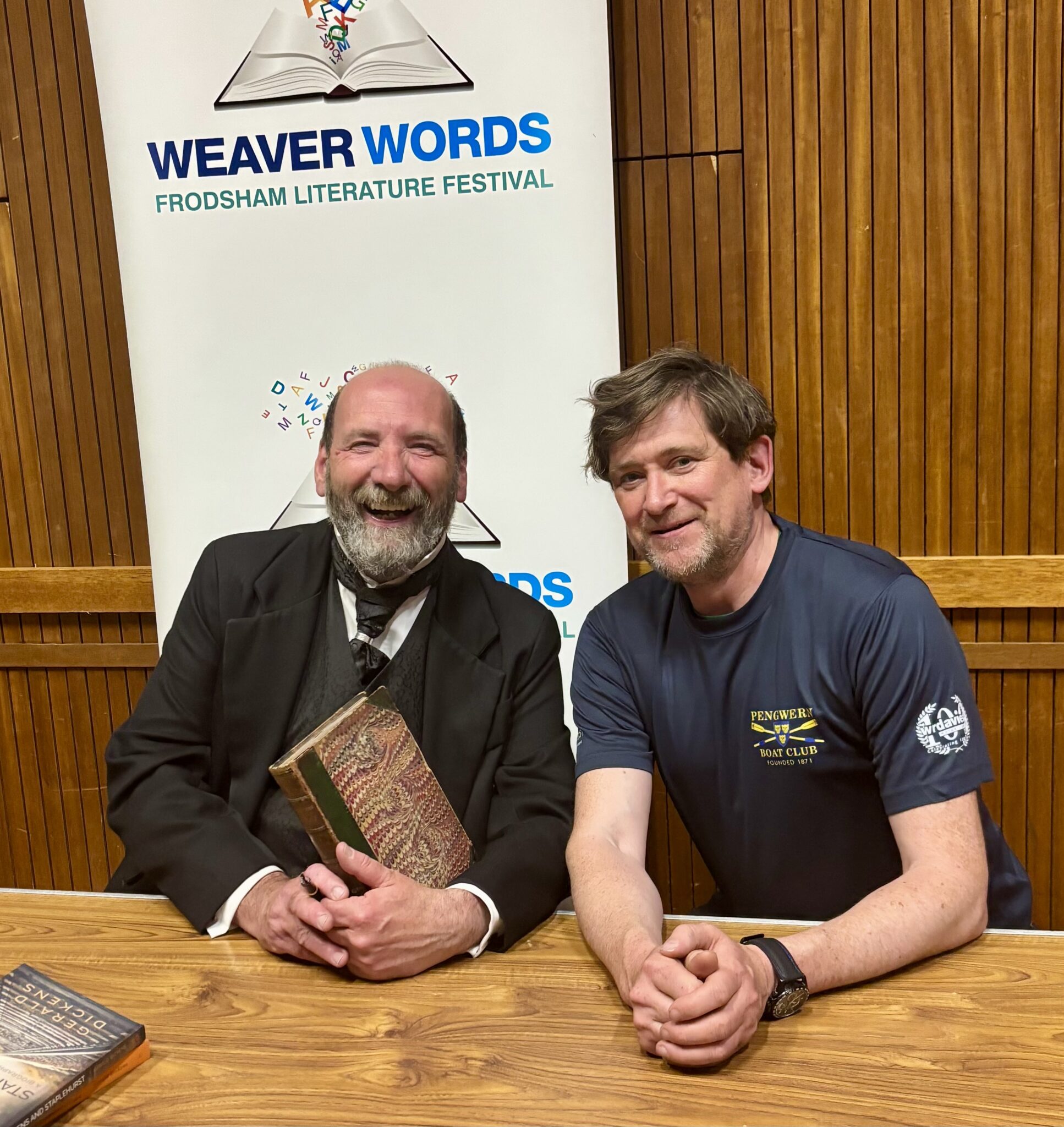

Last night, I had the pleasure of witnessing a truly mesmerising performance by Gerald Dickens — the great-great-grandson of Charles Dickens — who delivered a one-man show that breathed new life into his illustrious ancestor’s literary legacy. With only a few props and a masterful command of storytelling, Gerald captivated the room, weaving together the old and the new with elegance and flair. It left me not only applauding the performance but pondering the deeper question: is it right — or even wise — to follow in the footsteps of our forebears?

Some may instinctively recoil at the idea, dismissing it as nepotism — the privileging of one’s own based not on talent or effort, but on birthright. Yet I wonder whether this is always a fair criticism. Can following a family tradition be more about cultural inheritance and less about unfair advantage?

Tradition, Exposure and Informal Learning

Take Gerald Dickens, for instance. While the name may open a few doors, it was clear from his performance that what truly earned him admiration was his talent, dedication, and deep appreciation for the material. Being a descendant of Charles Dickens may have ignited the spark, but it was his personal commitment that made the performance shine.

A friend from school has a famous actor father and is currently appearing in a play at the King’s Head. He has struck out on his own from a very young age.

When children grow up surrounded by a particular profession, they absorb not just the technical language but the atmosphere, the values, and the rhythm of the work. Watching a parent mark essays at the kitchen table or prepare court bundles late into the night gives an insight that no textbook can match. This is not privilege in the cynical sense — it is proximity.

I didn’t follow my father into teaching, although I saw the rewards and frustrations of his career firsthand. But reflecting further, I realised that my grandfather had been a barrister and served in the Army Legal Service. Perhaps, in a way I had not fully appreciated before, I had followed in his footsteps. Not because of pressure or expectation, but because something in the air — the cadence of advocacy, the commitment to justice — took root in me.

Is This a Barrier to Social Mobility?

It is here that things get more complex. If the children of barristers become barristers, and the children of doctors become doctors, does this mean the doors are closed to outsiders? That depends on whether we create spaces for those without insider knowledge to gain exposure too. Mentorship schemes, work experience placements, and fair recruitment processes can level the playing field — not by tearing down family traditions, but by inviting others to build their own.

Seeing a parent or grandparent in action does provide advantages — of confidence, of networks, of understanding how the world works. But it does not preclude others from entering; it only underscores the importance of expanding access to those same opportunities for observation and inspiration.

The Right to Choose — or Depart — from Legacy

As Gerald told me, his own son works in the financial sector — a step away from the Dickensian tradition. And while part of me felt a pang of sadness at this break in the line, it is also a reminder that legacy need not be a chain. Just as we are free to follow, we must also be free to forge a new path.Family heritage should be neither a burden nor a shortcut, but a foundation — something to stand on if it lifts us up, or to step aside from if it does not serve us. The beauty of tradition lies not in slavish repetition, but in reinterpretation.

Conclusion: Footsteps, Not Footprints

In the end, perhaps the question is not should we follow in our family’s footsteps, but how we choose to do so. Are we merely retracing their path, or making it our own? Watching Gerald Dickens breathe new life into the words of his ancestor reminded me that legacy is not a script to recite, but a story to continue — in whatever voice we choose.

Whether we embrace our heritage or walk in another direction entirely, what matters most is that we do so consciously — with integrity, openness, and a sense of purpose. After all, even Dickens himself might have agreed: every life is a narrative, and every new chapter is ours to write.

Personally, I’ve found enormous fulfilment in mentoring those who don’t have family connections to the legal profession. As a diversity mentor, and a mediation trainer, I’ve seen how insight, encouragement and opportunity can help level the playing field. The legal world is at its best when it welcomes talent from every background, not just those with familiar surnames or legacy careers. Perhaps that is the real value of following in family footsteps — not just to walk a path, but to light the way for others too.