The legal world has been talking about orders made in divorce proceedings this week following two high profile judgments in the Supreme Court.

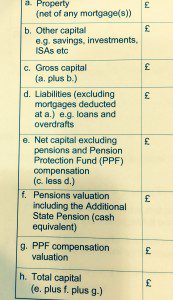

The cases concerned Varsha Gohil and Alison Sharland. The Supreme Court held that their divorce settlement and Court order could be re-opened on the basis that their spouses had deceived the Court about their assets in the divorce. The question is whether this principle applies to all cases in the civil courts such as following a mediation settlement, or just in the family Court.

Can a settlement be challenged at a later date if it is found that a party has not put all of their cards on the table and has withheld information deliberately? After all, people often settle early in order to prevent information coming out that might adversely affect their case.

In the case of Hayward v Zurich (2015) insurers tried to row back on a personal injury settlement. The Claimant had injured his back in an accident at work and the parties agreed to settle his claim upon payment of £134,973. Two years later his neighbours told his employers that he had completely recovered from the injury at least 6 months before the settlement was reached.

Insurers went back to Court to argue that the Claimant should repay the settlement money on the basis of deceit and fraudulent misrepresentation. The Court held that in deciding to settle the claim Insurers had taken the risk that the statements would not be proved at trial and paid a sum commensurate with that risk. By settling they had agreed to forgo the opportunity to disprove the statements. In entering into the settlement, the parties had implicitly agreed not to seek to set it aside at a later date. However, the Court said that the position might be different if the Claimant’s case had been fraudulent as well as ill-founded. If Insurers had settled in the knowledge that the claim might be fraudulent, however, and it did indeed turn out to be fraudulent, they could not then overturn the settlement, as they would have taken that risk into account. In this case, the Insurers had argued that the statements were dishonest before settling, or had not relied on them. To overturn a settlement on the basis of misrepresentation, a party has to show that they gave the statement some credit as truthful and had been induced into making the contract by a perception that it was true.

The judge said:

There is a wider principle at stake, that parties who settle cases with their eyes wide open should not be entitled to revive them only because better evidence comes along later”

Put simply, if a party settles a claim in the knowledge that the claim may not be true, they cannot turn round later and argue that they were misled. All cases involve an element of risk and evaluation of the prospects of the other party’s case being shown to be untrue. It is often one person’s word against another, supported or undermined by corroborating evidence.

The question is whether the Sharland and Gohil cases are likely to result in the Haywards case being overturned on appeal and settlements in the civil courts being set aside if non-disclosure or fraud is discovered afterwards.

The Courts have shown themselves reluctant to set aside settlement agreements, unless there are exceptional circumstances, which is clearly in the interests of the parties to obtain certainty and to avoid re-opening litigation.

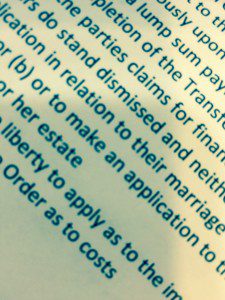

The Supreme Court found that in matrimonial proceedings if there had been non-disclosure, but it had been accidental or negligent, the other party would also have had to establish that the effect of the non-disclosure was such that the order made was substantially different from the order which would have been made (or agreed) if proper disclosure had been made, so there has to be an element of causation. However, where the non-disclosure was intentional, then, if there was such non-disclosure, order should be set aside, unless the other party could satisfy the court that the order would have been agreed and made in any event. In other words, where a party’s non-disclosure was inadvertent, there is no presumption that it was material and the onus is on the other party to show that proper disclosure would, on the balance of probabilities, have led to a different order; whereas where a party’s non-disclosure was intentional, it is deemed to be material.

It has to be borne in mind that family proceedings are different from ordinary civil proceedings in two respects. First, in family proceedings it has been clear that a consent order derives its authority from the court and not from the consent of the parties, whereas in ordinary civil proceedings, a consent order derives its authority from the contract made between the parties. Secondly, in family proceedings there is always a duty of full and frank disclosure, whereas in civil proceedings this is not universal.

The Court held that the reasoning of the Court of Appeal in the Hayward case does not apply to a case in which the dishonesty takes the form of a spouse’s deliberate non-disclosure of resources in financial proceedings following divorce. For the spouse has a duty to the court to make full and frank disclosure of their resources, without which the court is disabled from discharging its duty under section 25(2) of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 and any order, by consent or otherwise, which it makes in such circumstances is to that extent flawed. One spouse cannot exonerate the other from complying with his or her duty to the court.

Although honesty about one’s resources is crucial in family proceedings and there is a duty of full disclosure owed to the Court, it seems to me that there is a duty owed to the Court in Civil proceedings to be truthful and the Court should not uphold a settlement that has been procured fraudulently, so I anticipate that the Supreme Court will take the same line in relation to Civil proceedings and the Hayward case.

Disclaimer: The information and any commentary on the law contained in this article is for information purposes only. No responsibility for the accuracy and correctness of the information and commentary or for any consequences of relying on it, is assumed by the author. The information and commentary does not, and is not intended to amount to legal advice to any person on a specific case or matter. The article was written on the date shown and may not represent the law as it stands subsequently. For the avoidance of doubt, the views in this article are personal to the author and not attributable to any other individual or organisation.